There's More to Explore Here: Space Between Stories

Our brains are natural storytellers, constantly transforming chaos into order. This cognitive shorthand usually serves us well - we don't need complex calculations to understand that brake lights mean "stop" or that a smile typically signals friendliness. These instant narratives run in the background like efficient little programs, helping us navigate daily life without getting overwhelmed by the sheer complexity of existence.

It's essential for survival - if we had to deeply analyze every situation, we'd be paralyzed by the cognitive load. Research suggests that we make up to 35,000 decisions each day.. Our brains excel at pattern recognition and quick story creation, freeing up mental resources for more demanding tasks.

The Pattern-Making Mind

When reality presents us with gaps, our minds rush to fill them. A child hearing their family is moving might wonder if they're leaving Earth entirely - their understanding of geography limited to "home" and "space" from picture books and cartoons. A teenager told they're "different" might spend years constructing elaborate theories about what that means, each interpretation shifting with new information and experiences.

A job candidate receiving a "we'll be in touch" might spiral through dozens of interpretations in the aftermath. Slight pauses from an interviewer take meaning. And a few hours later, the candidate has constructed entire futures and foreclosed others, all from fragments of information.

Even in casual social interactions, our minds work overtime to create coherent narratives. A friend's delayed response to a text message becomes a story about the entire relationship.

Analyzing all of those decisions and associated stories is impossible. It isn't uncommon for world leaders and CEOs to drastically reduce their wardrobes to only one outfit in an effort to "combat decision fatigue."

Steve Jobs' black turtleneck is probably the most famous example. Most people created a simple story about this: personal branding, the eccentric tech visionary with his signature look. The reality, according to Walter Isaacson's biography, was more complex. Jobs was inspired by uniforms at Sony in Japan, where employees wore standardized clothing to forge post-war bonds. He actually tried to introduce a corporate vest for all Apple employees (which they promptly rejected). The turtleneck was essentially the remnant of a failed experiment in corporate unity.

Simplified narratives - "it's just branding" - help us process information quickly. Some other examples of the one outfit wardrobe: Mark Zuckerberg's grey t-shirts become "trying to copy Jobs," Elizabeth Holmes' black turtlenecks become "intentionally mimicking her idol." The truth behind these choices might be more nuanced, but our brains prefer the shorter story. It's more efficient. One clear narrative is easier to remember than a complex web of motivations, influences, and circumstances.

Digital Acceleration

The pressure to understand immediately has never been greater. Our hyper-connected world demands instant reactions and rapid conclusions. Social media feeds and 24/7 news cycles ask news pundits (and us!) to form opinions about events still unfolding, to categorize experiences we're still processing, to reach conclusions before all information is available.

I'm appreciative of Last Week Tonight's episode that aired just after the 2024 presidential election. In it, John Oliver highlighted how quickly democrats threw blame at fellow democrats and minority groups on the heels of the election loss. It's a pattern we've seen before - the rush to explain complex political shifts with simple narratives. "This group didn't vote enough." "That strategy was wrong." These quick explanations might help us feel like we understand what happened, but they often oversimplify complex social and political dynamics.

And this acceleration doesn't just affect how we process world events. It changes how we experience our personal lives too. A relationship ends, and friends immediately offer explanations and advice. A job change occurs, and everyone has an opinion about the industry's future. The space needed for genuine reflection gets compressed into smaller and smaller windows.

This pressure to immediately understand and explain extends into our most intimate experiences of loss. When faced with profound grief - where the stakes are highest and the pain most acute - our drive to make sense of things doesn't diminish. If anything, it intensifies, sometimes with devastating consequences.

When Assumptions Harm

But what happens when this same drive for simple explanations collides with profound loss? Our need to make sense of things doesn't stop when the stakes get higher - if anything, it intensifies.

Sometimes people come to therapy to process grief. And in addition to my day job, I volunteer as a grief counselor for Camp MAGIK, a bereavement camp for children who have lost close family members. In both of these settings, I witness how quickly people create narratives to explain the inexplicable. "It's my fault" becomes a common refrain - a devastatingly simple story to explain something too complex and painful to process all at once.

From the outside, it's easy to recognize that people die in unfathomable ways, often in ways that make no sense. Even someone who can recognize that it isn't someone else's fault that their loved one died might struggle internally with the same thing. In the moment, "it's my fault" consumes. It's a quick story for the incomprehensible, but one that can cause immense harm.

Interpretations, meant to help us process experiences, can calcify into damaging beliefs that shape our future experiences. They become self-fulfilling prophecies, not because they're true, but because they're the stories we had available when we needed to make sense of something painful or confusing.

The definition for grief I've adopted is: "The feelings we have when we've lost someone or something." Those feelings can be sadness, joy, anger, relief, anxiety, fear, everything, and nothing. There is no "right" way to grieve, nor is there a correct way to communicate grief. You may not know how you feel. You may never know. That's okay.

In a lighthearted interview between Steven Colbert and Keanu Reeves, Colbert jokes around asking, "What do you think happens when we die, Keanu Reeves?" The audience laughs. Reeves, who has been extremely open about his own grief throughout the years, replies, "I know that the ones who love us will miss us." I think about that quote from time to time. "Miss" is an ambiguous term.

Value in Uncertainty

People come to therapy for a variety of reasons. A common one is to make sense of stories: current events, societal norms, cultural values, personal narratives, and so much more. Therapists can't guarantee or offer certainty in this capacity.

I wish we could.

What we can do is hold space for individuals making sense of their own stories.

In practicing therapy, I use a generous number of narrative therapy techniques. For example, whenever I've run long-form process groups, I've encouraged members to write and share their personal timeline - from birth until the present. Commonly, the response to that request is, "That will take forever! I'm _____ years old!!" My response is "You're right. Just include the important parts then."

Or in grief groups, there's a time for individuals to share how their loved one passed. So they tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. And with that end, the person sharing will verbally proclaim "The End." - That closure is important.

The group listens. Sometimes all someone needs is to be heard; other times, they'll ask for feedback from the group. Some things I've heard in feedback:

"You started with high school, but I was wondering what happened before then?"

"Hey, that wasn't your fault. At all."

"You didn't deserve that."

"I don't remember that much about my childhood. Did someone tell you about yours?"

"I relate to what you said about ______."

"I thought you were going to talk about _______, but you skipped over that?"

The gaps, the "unimportant parts" are sometimes holding the heart of a narrative. Not always, but sometimes.

Breaking free from premature conclusions isn't about stopping natural meaning-making processes. It's about developing the capacity to hold space for uncertainty. To say "I don't know yet" or "This story is still unfolding."

Some of our most important growth comes from sitting with uncertainty, from accepting our understanding to be works-in-progress rather than final editions.

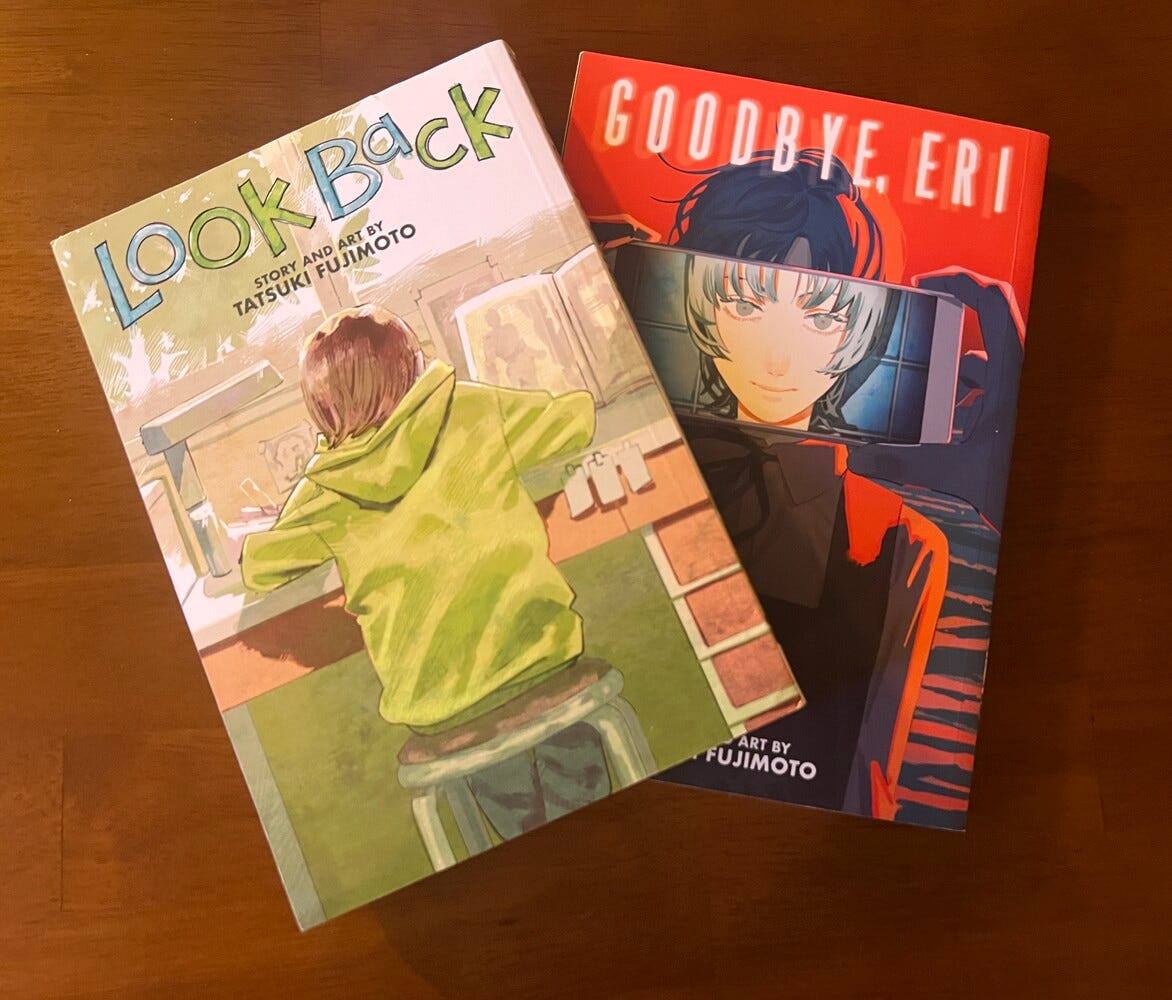

I recently read two manga one-shots: Look Back and Goodbye, Eri. It's overwhelmingly evident that Tatsuki Fujimoto personally understands loss, grief, and the process of rewriting narratives (something you'd hope an author would excel at). Both of these manga heavily explore themes I've written about in this article, and I couldn't recommend them more. My copies live in my therapy office.

A film adaptation of Look Back released earlier this year and is currently streaming on Amazon Prime. Heck, it might be my favorite movie from this year - and it's only 58 beautiful, emotionally devastating minutes.

I saw it in theaters and then re-watched it over the holiday, which pushed me to consider and write this article.

If you watch the movie and/or read either/both of the manga, I'd love to hear your thoughts.

And I didn't have a clean transition to include this, but a current uncertainty of mine: Zuck's newest threads and Gen-Z hairstyle.

And his T-Pain collab.

Huh.

Best,

Will Ard

LMSW, MBA